(Note: This is a repost of an earlier post.)

This account, narrated by the 27th Sakya Trizin Jamgon Amnye, highlights the potential danger of practicing the kumbhaka (bum can) technique recklessly or with the wrong motivation. Although he states that the person died while practicing kumbhaka (bum can) during the stage of prāṇāyāma, he recounts the story in the context of explaining forceful yoga (haṭhayoga). This suggests that he was referring to a Ṣaḍaṅga yoga’s haṭhayogic [forceful] method..

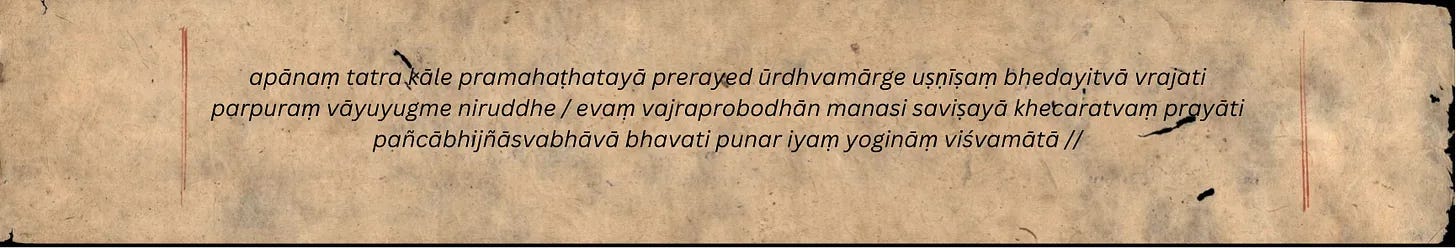

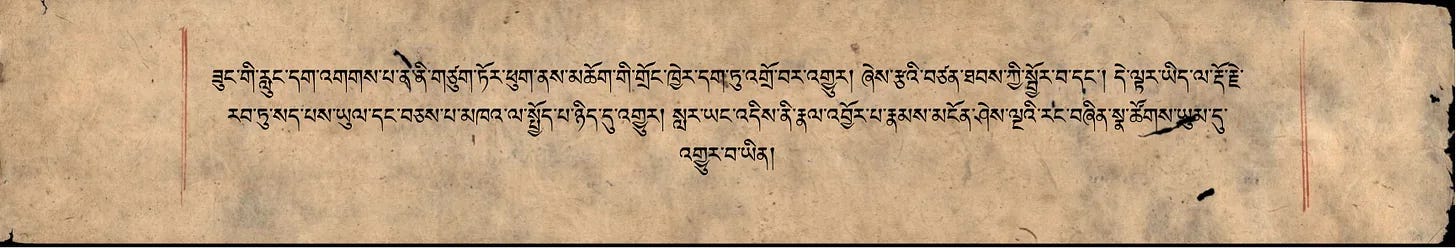

In the haṭhayoga section on prāṇāyāma, the practice describes a forceful method aimed at piercing the crown of the head (uṣṇīṣa) by violently propelling apāna vāyu upward, thereby sending the prāṇa upward toward Khecara—the celestial realm. The Ṣaḍaṅga Yoga text by Anupamarakṣita, translated by Francesco Sferra, mentions this haṭhayoga practice.

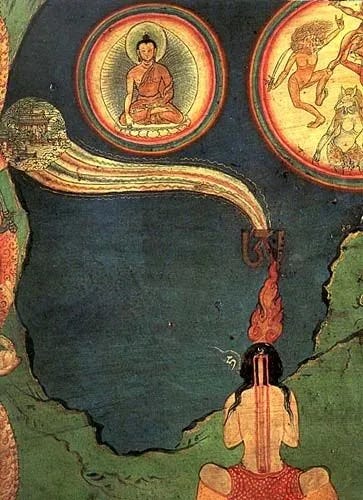

At this moment, the yogin must push the wind of the apāna (vāyu) with extreme violence (force) in the way that is directed upwards (urdhvamarge). After having perforated the uṣṇīṣa (crown) and restrained the two winds (of the left and right channels), this power reaches the "supreme citadel". Thus, through the awakening of the vajra, this power along with the objects, attains the state of khecara in the mind and then becomes the yogins' universal mother endowed with the five kinds of super-knowledge.

However, Jamgön Amnye cautions: "Phowa, the ejection of consciousness into the Khecara, should only be practised at the moment of death; if it is done at the wrong time, as the saying goes, it will kill the gods"—with “gods” here referring to the physical body, considered the dwelling place of hundreds of deities. He further advises: "When practising prāṇāyāma, if you experience pain or heat around the crown of your head, do not continue while in pain. But also, do not simply stop—rather, seek a remedy for that discomfort."

In Ṣaḍaṅga Yoga’s haṭhayoga practice, there are advanced breathing techniques—such as kumbhaka—where the practitioner forcefully propels the breath upward from the lower abdomen, like an arrow. However, in such practices, one is meant only to feel or visualize the breath piercing the crown of the head—not to force it physically. The following account tells of two deaths that occurred during the practice of prāṇāyāma: the first seems to have been a timely and proper execution, while the second appears to have been a misapplication.

There was a practitioner named Rinchen Chödar, an Abhidharma follower and also a student of mine. Later, at Trophu Nyenkhar Sangdzong, he received Ṣaḍaṅga Yoga (sbyor drug) teachings from Lama Tashi Pal. At the same time, he was observing the monthly practice of Amoghapāśa on the eighth day. During one such observance, while performing the prāṇāyāma (srog rtsol) component of the practice, he entered kumbhaka (bum can) and passed away instantly, seated upright in meditation posture.

When his Dharma friends found him, they took his body to a mountain, ritually dismembered it, and offered it to vultures. Wherever the vultures carried his flesh, rainbows appeared in the sky. Upon hearing the news, senior yogis and geshes remarked, “One junior monk has humiliated us all.”

In another case, three students were receiving teachings on prāṇāyāma from Chöje Kunpangpa. They made a pact, saying, “If we die while practicing prāṇāyāma, we will attain khecara (the celestial realm), and there is no higher goal.” With this resolve, they engaged in the practice. One of them died immediately due to a rupture at the crown of his head. The second entered a coma-like state for three or four days before passing away. The third survived, revived only after undergoing a ritual to remove obstacles.